|

Michael

Tanner

my teacher

15 April 1935 – 3

April 2024

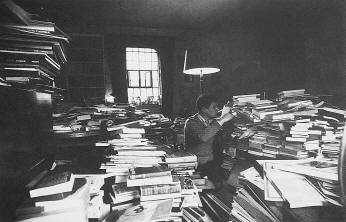

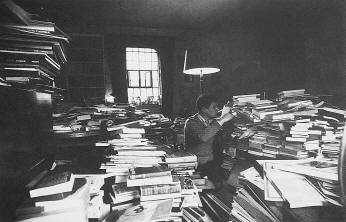

The title image is taken

from "Likenesses" by Judith Aronson,

a superb book of portrait

photographs

published in 2010 by the

Lintott Press

in association with Carcanet

Press, Manchester:

ISBN 978 1 85754 994 2.

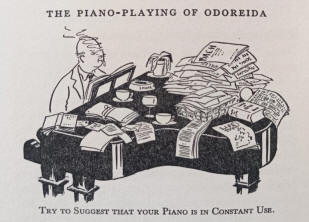

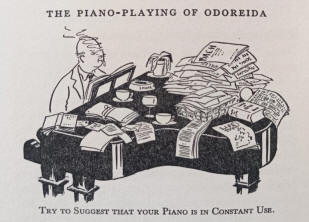

The illustration of Odoreida’s piano is by Lt.-Col. Frank Wilson

and appears on p.56 of

“Supermanship” by Stephen Potter,

published in 1959 by Rupert

Hart-Davis.

Both have been

lifted with heartfelt if proleptic thanks.

Posted on 12th July, this piece is possibly subject to revision as

reflections appear;

a concise version has appeared in the autumn 2024

issue of Opera Now.

20 minute read

éYou can download a PDF of

this present version

here.

When he died, in

early April this year [2024], Michael Tanner was very nearly 90

years old; for many readers he had been the opera critic of The

Spectator for quarter of a century, and for others their Moral

Sciences mentor at Cambridge over nearly forty years. Saddened

to learn the news, I found I wished to put down some thoughts, which

follow.

At the end

of my first year reading philosophy at Cambridge, in 1975, my

director of studies, assessing my interests and inabilities, told

me, “I think you’re one for Michael Tanner next year.” I had

never heard of Dr Tanner. Yet this verdict, itself also much

chattered among my contemporaries, came with an eyelid

flicker suggesting a plot. Be it poisoned, glittersome or

leaky, I had been handed something akin to a chalice, if not a grail.

In the autumn I took up this vessel. Entering his rooms for

the first time, sidling down past its overflowing contents, past an

orange-shaded standard lamp, to a zone of compressed habitation in

front of the gas fire-place, to meet the man in the red jumper and

leather trousers, of eagerly poised, oft-tilting head, I felt

completely at home. Fortunate enough to have a Study in my

parents’ home, I too knew a more or less square room, with a

fire-place, a piano, shelves and tables piled or laden with

innumerable books and LP recordings, and narrow access down the side

of it all; with one difference — in mine you could see the floor.

Tanner and I seemed to pick up from an earlier conversation that had

never in fact happened, of course, and my 2 o’clock supervision

ended around eight in the evening.

That was to be below the average duration thereafter and it was not

unusual only to manage back to my room at 2 or 3 in the night,

sometimes by climbing in over the bike sheds at the back of

Pembroke. Occasionally we took an evening meal together,

possibly in the so-called Grad-Pad, but I remember rather few of

those; the more usual pattern was that I would bring a pineapple and

a bottle of whisky. He, of course, no longer could drink, but,

like Colonel Sternwood, he was happy to watch me and would share the

pineapple. We also shared a passion for spade-worthy dark

coffee made in a Bialetti machine over a gas ring by the fire, and

served in large cups in the form of chamber-pots, fashionable at the

time, decorated perhaps with Victorian advertisements for corsets.

The room was an inner sanctum in so many ways, a live shrine, so to

speak, of a passion for the flowering of our civilisation — “a

twentieth-century version of Hume’s library” he once called it —

represented by those musty, almost holy whiffs of the paper of books

and the cardboard of record sleeves, competing with pagan whiffs of

that macadamesque coffee and what I am sure was inexpensive but

generously applied eau de Cologne.

What on earth did we talk about? For we did talk and talk; it was

not always ‘philosophical’ — my essay was a springboard and while it

was always clear he had read it carefully, it was never annotated —

but could be peppered with gossip. His ability to offer a

concise ‘put-down’ was very sharp, either of a contemporary in the

faculty or from a wider field. Once, holding a copy of the

latest volume by Lacan he frowned: “Just shows you how fast the

French have to run to stand still.” Not quite gossip but of

the ilk in tone. Of a distinguished Germanist I had also

studied with, “He’s so vain he wears his hair to look like a

toupé.” Michael had a subtle and ironic understanding of

vanity, based finely on a certain glimpse of self-observation.

In my day he fancied he resembled James Dean, of whom he had a very

large photograph on the door leading to his bedroom. I made

the mistake of seeming unconvinced.

Though he showed great understanding towards me when I went through

a standard-issue crisis, we seldom spoke on personal matters.

On the rare occasions when he spoke of his alcoholism, then defeated

by drastic but long-lasting treatment that had even been the subject

of a profile in The Sunday Times, I think, I recall that his abiding

memories of it were the problems of dealing with all the empties,

in a suitcase in the woods, and of dealing with the tendency to inanity on the part of his

fellows at High Table as they downed drink at dinner. He gave

two-hour lectures and brought a thermos in his briefcase — strong

coffee, but a legacy of the erstwhile need for surreptitious drink.

Amidst the talk it is my recollection that it was quite rare for us

to share a recording together as if at a concert or recital, and

that if we did it was of something of the highest vibrancy to our

spirits — a recent performance of Die Winterreise that Hans

Hotter had given in Tokyo, an unofficial tape of the Busch Quartet

in Op.130 come to mind. The underworld of such tapes was the

work of a global network of enthusiasts; recording companies did not

approve, though it was known that Callas, for instance, did

encourage these ‘live’ tapes to flourish, even of her

under-estimated rival Leyla Gencer, much to our benefit now that

copyright worries have subsided and allowed such material to be

released officially. One collector, possibly in Norway, had an

exhaustive collection of Flagstad pre-war; another, in America, had

the tapes from after the war; Michael put them together and managed

thus to have the whole career. The BBC had a very sloppy

policy of wiping tapes, and subsequent official issues of gems such

as Goodall’s Mastersingers and Horenstein’s Das Lied von

der Erde came about solely after an amnesty with Tanneresque

enthusiasts who had taken the first live transmission. In

reverse, the Ring cycle that he used for his weekly evening classes

on the tetralogy, to which I was not invited, came from tapes that had been smuggled out of

Broadcasting House for a night, to be copied. Or was that the

Toscanini Brahms cycle from the Royal Festival Hall? (Both

have now been issued, some three decades after, by Testament.)

At my first supervision I was so pompously proud to have been taken

on as his pupil, ‘this year’s protégé’ as people had it behind my

back, that I assumed the slowly turning tape deck was there to

record our conversation. No, it was Shura

Cherkassky’s lunchtime recital from Manchester after all.

This ancient cluttered chapel contained very large photographs of

D.H.Lawrence and Schoenberg, as well as James Dean, standing like

statues of saints amidst the rubble of learning and listening.

Frederick Hartt's monumental book on Donatello was there, propped by

a very large studio loudspeaker. The

record collection was both deep and wide. That’s to say, he had a

wide range of love of music, but also had a passion for how

different performances of that music enhanced its richness.

Wide or deep, his love could bubble into sheer glee — I recall the

day the stall on the Market had put the Bob Dylan Budokan 1978

LPs on sale, or when Murray Hill issued the Furtwängler Milan

Ring, news that quickened his step to a trotting gait, wearing

his collectors’ spurs. Be it of Dylan or Furtwängler, record collectors all have their sundry

‘versions’ fetishes, but in few if any cases does one feel that so

much is at stake as when Tanner would pull out an LP, not even

necessarily some extreme rarity none of us could hope to find, and

promote its glory. He bought LPs of artists he did not care

for — such as Fischer-Dieskau, Karajan, Sutherland — on the basis of

“knowing the enemy”. Of his heroes however — in that

congruency they would be Hans Hotter, Furtwängler and Callas — he

could unfailingly dig out the clinching snippet to leave you in no

doubt. And on top of all that, knowing it would alarm people,

he would explain that “the tapes are the hub of my collection.”

We made many record-buying excursions, across Cambridge or in

London, and, in my second year of study with him, when I had a car,

out to Norwich or even Lowestoft. My haul might come to nearly

100 LPs, usually less than half his ‘bag’. You must remember

that there was no internet, nor easy advertising by the little

specialist shops who in any case seldom had anything as

technologically sophisticated as a list of their stock. So,

each excursion was an adventure. We would set off for Ives’ in

Norwich, for instance, not knowing if the haul would be few or by

the dozens. Like any true collector, Michael did not need a

list of his own collection, and could spot a variant at a glance;

and he would share my excitement when at last, after years, I

happened upon an LP he had long wished for me. For some reason,

Cherkassky’s Beethoven Op.111 comes to mind, not quite a rarity,

let’s say an oddity: “Oh yes,” he chewed to me from another stack,

“just wait till you get to the istesso tempo.” He

shared my excitement when I graduated to a ten-&-a-half-inch reel-to-reel

deck, and made me tapes of my favourite least available glories.

That generosity was most evident in the way in which Tanner allowed

undergraduates to borrow LPs from his collection, if they turned up

during a fifteen minute window before dinner in Hall. During

my extended supervisions I was often a witness to how succinctly

Tanner would guide their exploration of the repertoire, or fashion

their taste in performance, sometimes with a withering opinion that

was more directed at the overwhelming conventionality of classical

music reviewing, than at the poor beginner’s bewilderment. On

another level he told me once how he had started to play the 1939

Mengelberg performance of Bach’s St Matthew Passion to

Raymond Leppard, a doyen of ‘authenticity’ in performance — who told

him he would leave the room if Michael persisted he listen on.

“Not a ‘musician’ in our sense,” he uttered to me from behind the

lamp shade.

His no-nonsense, robust and focussed intellect — after all, I was

there to study philosophy, at least some of the time — was balanced

by a complete sensitivity to the absurd. He remains more or

less the only peer with whom I have had proper conversations about

Stephen Potter’s gamesmanship books, he relishing that Odoreida’s

cluttered piano in Supermanship, a suitably Nietzschean title

by the

way,

so resembled his own, ‘in constant use’. This sense of the

absurd (a word he relished to utter, the second syllable coming with

a torque that suggested the fashioning of a dowel) was of course

laden with serious intent, belonging to his ingrained disdain of

what we usually call ‘authority’; an ironic disdain given the rank

he achieved as an authority not least on Wagner and Nietzsche, not

to mention in the college hierarchy.

It was clear from his (very infrequent) recollection of National

Service, in RAF Intelligence, in Germany, that he had no higher an

opinion of military authority, or any other officialdom, than Spike

Milligan. Not that ‘disdain’ was always strong enough: his

masticatory declamation gave words such as ‘loathe’ the resonance of

a strangled neck, as he despaired of people’s possible sheer

wrong-headedness or sad tendency to unthinking stupidity. way,

so resembled his own, ‘in constant use’. This sense of the

absurd (a word he relished to utter, the second syllable coming with

a torque that suggested the fashioning of a dowel) was of course

laden with serious intent, belonging to his ingrained disdain of

what we usually call ‘authority’; an ironic disdain given the rank

he achieved as an authority not least on Wagner and Nietzsche, not

to mention in the college hierarchy.

It was clear from his (very infrequent) recollection of National

Service, in RAF Intelligence, in Germany, that he had no higher an

opinion of military authority, or any other officialdom, than Spike

Milligan. Not that ‘disdain’ was always strong enough: his

masticatory declamation gave words such as ‘loathe’ the resonance of

a strangled neck, as he despaired of people’s possible sheer

wrong-headedness or sad tendency to unthinking stupidity.

Indeed, his manner of declamation was part of the point.

Perhaps it is intrinsic to most lecturers that their style resembles

in some way the lesson they seek to impart. Of course.

But again with Tanner one sensed that more was at stake. And I

am tempted to think that this was achieved by a sort of back-handed

insouciance — as if he counter-balanced the vital importance of

these skills, tastes, passions, values and all, with a recognition

that most people don’t care, perhaps cannot care, and, well, that’s

their loss. He was an evangelist by example, not by speech.

I have no recollection of ever anything being ‘rammed down my throat’.

On the contrary, I have an indelible memory of him, as so often, in

that red jumper and craning his head round the lamp, gazing,

imploringly, lost for words — yes — at the Kyrie of the 1935

Toscanini Missa Solemnis or Hotter delivering the

Karfreitagszauber. He knew well the seventh proposition of

Wittgenstein’s Tractatus, that there are things of which one

cannot speak. But must all the same.

At this moment we might address the subject of Tanner’s relationship

with Wittgenstein and indeed with philosophy in general. Some

might start and ask, “There was one??” The answer can be simple or

complex, the one not excluding the other. The simple answer is

that he taught what the gritty philosophers regarded as a soft

subject, aesthetics, rather than hewing the coal faces of logic or

ontology, where you have to wear goggles at the face. And his

speciality, in those days quite innovative in itself, was to look at

the so-called ‘continental’ tradition, the German romantics in

particular, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche especially. The

superficially assumed disconnect of most of these writers to the

mainstream flowing from Berkeley, Locke and Hume, gave his course the

character of a backwater. Yet this is where Wittgenstein

strikes a dischord; on the one hand, Wittgenstein had become the

pivotal figure in hard philosophy in the Anglo-Saxon field, yet was

a figure whose roots in the German tradition such as Schopenhauer

and Nietzsche were underestimated, and whose almost poetic power was

at utter odds with that other tradition.

A fine television documentary on Wittgenstein by Christopher Sykes,

later to become Hockney's sympathetic biographer, first aired in 1989 and

now available in a VHS home tape

version on YouTube

here,

features Tanner, in his study, cushioned among books, elaborating

Wittgenstein’s philosophical progress with language and meaning.

It seems aptly characteristic — a word which he pronounced as

kahra’tistick — that he is seated facing sideways to the camera,

leaning round to the viewer, his fine, open fingers explicating

clarity or flicking a cigarette. His exposé is perfectly judged

for a television audience, and we witness his signature clarity and

judiciously unexpected phrasing. We also come up against

councel given by Wittgenstein himself, to the young Norman Malcolm,

when Malcolm was offered a philosophy teaching post in America:

basically don’t — you will be asked to cheat yourself, and others.

Malcolm disobeyed, as did Tanner. But as a teacher of

philosophy, Tanner took Wittgenstein’s warning completely to heart.

Let me explain myself better. In various obituaries I noted

that Tanner was referred to as a music or opera critic — true — and

as a philosopher — untrue. As widely read in philosophy as it

would be possible to be while ‘having a life’, as we’d say, he was

superbly able to lay these thoughts and thinkers before you, as well

as offering ideas towards your ability to appreciate or criticise

them. Many of his writings on Wagner, for instance, or

Nietzsche, reveal his superb ability to be completely fair-handed —

while despatching a text or writer to a deserved, dusty oblivion of

nonsense. Hence he admired my first essay, on Richard

Wollheim’s Art and its Objects, as a splendid ‘hatchet-job’,

then a phrase much in vogue in some philosophical quarters.

His variations on reductio ad absurdum were Beethovenian in

effect. But he did not philosophise. There is no

doctrine or seminal insight or crucial tool of his that has lingered,

either as a seed or a plague upon the field of philosophical

endeavour. Nor had he any pretentions to having contributed in

that way. I do not know, but I cannot believe he had ever

expected to be offered a Chair in philosophy at Cambridge, he knew

too well the then emerging requirement for productivity in print

that that entailed. And in that sense he adhered nobly to

Wittgenstein’s fear that what would be expected was just such

churning, as illuminating and insightful as a cement mixer, and did

no such thing.

Instead, nobody interested by the creations and insights of

Schopenhauer, Nietzsche or Wagner can afford to overlook Tanner’s

cogent and vivid accounts — including sundry introductions to

translations. His guide to reading Nietzsche that prefaced the

CUP translation of Daybreak, in its first edition, is one of

the finest elaborations we have; in later editions of course it was

replaced by something less quirky and of little merit. Both in his lectures and in his

writings, however, he achieved a very delicate balance between

exegesis and — well, something like enticement. He encourages

you to think for yourself, though that hackneyed phrase does not do

enough, for it underplays the way in which Tanner expected you to

engage with the texts at stake. He had doubts about how

effective it was to the world’s enlightenment that people study such

matters, but he had no doubt about the importance of such matters.

How the inner self is to engage with the outer — perhaps even indeed

whether — had, for Michael, a self-evident answer, and his life’s

mission was to make it a shade evident to others.

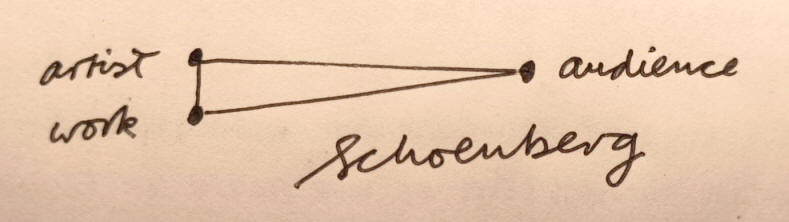

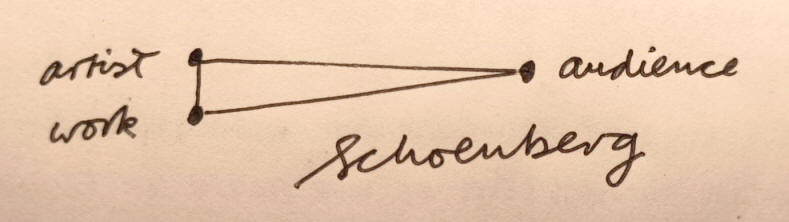

I do recall one idea of his however that has never left me: we

called it The Tanner Triangle. Its principle was that you

assign each point of a triangle to a given artist, his work, and the

audience. The length of the lines between each point

represented the ‘closeness’ between these aspects. Thus for

instance with a cerebral composer such as Schoenberg, the two lines

between audience and the rest would be rather long, but the line

between artist and work very tight and short.

As the basis for

a pretentious after-dinner parlour game this has some potential,

doodling the triangles for Proust or Dittersdorf, but

its value is hidden by that superficiality: for its value is to reinforce the

idea of the importance of the audience in the whole process — our

very own importance in the whole business of deep communication —

reminding us that this variable gives life to it all. That

this ultimately reflects the later Wittgenstein’s thoughts on

language as social tool is something to be elaborated elsewhere; that this vital

spring in the life of artistic expression was central to Tanner’s

passion for the arts, on the other hand, is something that I am

seeking here to celebrate. As the basis for

a pretentious after-dinner parlour game this has some potential,

doodling the triangles for Proust or Dittersdorf, but

its value is hidden by that superficiality: for its value is to reinforce the

idea of the importance of the audience in the whole process — our

very own importance in the whole business of deep communication —

reminding us that this variable gives life to it all. That

this ultimately reflects the later Wittgenstein’s thoughts on

language as social tool is something to be elaborated elsewhere; that this vital

spring in the life of artistic expression was central to Tanner’s

passion for the arts, on the other hand, is something that I am

seeking here to celebrate.

Back in the day, in my spasmodic guise as an arts critic, I was sometimes

asked to give a talk on the rôle of the critic, especially the

critic of performance. Some thought this a beastly task,

others vacuous. My gist was always simple: the job is to

create an audience, so that those who were there might relive their

experience maybe with richer or wider or just different enthusiasm,

ears & eyes, and those who hadn’t attended just kick themselves.

Nobody had trained me to hold so lofty or daft an ideal, it just

seemed to be right and to form some sort of buttress against the

pointlessness of being rude. It was only later that I realised

that my mentor in this regard had been Michael Tanner and that he had never said or suggested any

such thing.

Of all my teachers, from Kindergarten to degree, Tanner is the one

of whom I’m stuck to recall something he actually taught me.

Yet he was perhaps my greatest teacher. And that’s just it.

He opened doors, and cajoled. His criticism appealed, like

Cromwell, “in the bowels of Christ”, to the possibility of the

sublime, towards the fullest realisation of the expression of art,

towards an understanding that might, just might redeem our frail

misunderstandings and lazy complacencies — all, as he once put it in

a short radio talk, for a “temporary warding off of ultimate defeat”.

Few have his urgency of intelligence that matches and indeed

dovetails with what we suppose to be the usual urgency of sensuality.

His fascination was with that process, and his teaching by example.

Yet to the idea of being in some way an aesthete he told me once,

curling round with conscious irony from behind that lamp, “I can’t

stand that poofy attitude to art.” For art was in no way an

accessory, but a necessity. In this way of life he differed

profoundly from most of his fellow critics.

Such manly pessimism, as well as the Sisyphus-like heroism needed to

survive it, had its voice for Tanner in the world of German

romanticism, the writings of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche and indeed

of Wagner, whose thinking Tanner took as seriously as the music.

(I might observe here that though he is most of all taken as a prime

Wagnerian, he once told me, “I can never quite escape the feeling

that the greatest opera of all is Fidelio” — which I took to

be a confession of a closet optimist after all.) Despite later

volumes, I still regard his extended essay in the 1980 Faber

Wagner Companion as the finest introduction to the composer,

because of his conscientious exposition of the intellectual

procession of the dramas. It is a very long contribution which

Tanner had had to fight to have included without cuts.

But it is very strong, at once rich in research and knowledge, and

warm in personal commitment. Indeed, his exposition of Die

Meistersinger, debunking the supposed antisemitism of the

character of Beckmesser, caused Leonard Bernstein to summon him to

the Savoy, whereupon the great man told Tanner that he had now

renounced his refusal to conduct the opera — but that nonetheless it

was now too late for him to take it on. I believe their

discussion also included Bernstein’s more complicated conversion to

Parsifal, which he also had never chosen to conduct.

Tanner’s telling of the encounter was memorable for his disdain of

the monogrammed knitwear.

Tanner’s various writings on Nietzsche press home the point that there is

no ‘philosophy’ to be found, no Dummies'-Guide crib, rather a way of thinking, which was at

heart what made Tanner himself tick in that fetching, wise and

frequently witty plurality of single-mindedness with which he

welcomed all human expression that expanded his life and, if we make

the effort and pay attention, ours. Too bloody bad for

you if you don't.

é

return to top é

|

As the basis for

a pretentious after-dinner parlour game this has some potential,

doodling the triangles for Proust or Dittersdorf, but

its value is hidden by that superficiality: for its value is to reinforce the

idea of the importance of the audience in the whole process — our

very own importance in the whole business of deep communication —

reminding us that this variable gives life to it all. That

this ultimately reflects the later Wittgenstein’s thoughts on

language as social tool is something to be elaborated elsewhere; that this vital

spring in the life of artistic expression was central to Tanner’s

passion for the arts, on the other hand, is something that I am

seeking here to celebrate.

As the basis for

a pretentious after-dinner parlour game this has some potential,

doodling the triangles for Proust or Dittersdorf, but

its value is hidden by that superficiality: for its value is to reinforce the

idea of the importance of the audience in the whole process — our

very own importance in the whole business of deep communication —

reminding us that this variable gives life to it all. That

this ultimately reflects the later Wittgenstein’s thoughts on

language as social tool is something to be elaborated elsewhere; that this vital

spring in the life of artistic expression was central to Tanner’s

passion for the arts, on the other hand, is something that I am

seeking here to celebrate.